Other parts of this series:

In our previous post, we shone a light on the shipping sector’s hidden sustainability problem: end-of-life vessels, and the dangerous and polluting shipbreaking practices involved in their disposal. We also explored what makes this problem so intractable – namely that shipowners benefit financially from scrapping their ships in substandard yards, generally in the third world, since these can offer the highest scrap prices.

There is little that insurers can do to address this directly. Few vessels end their lives as insurance write-offs. And, while cover can of course be denied to vessel operators that lack environmentally sound ship-recycling policies, nothing stops these simply shopping elsewhere. All of which raises the question… Might insurers play an indirect role instead?

To answer this, we must acknowledge a simple truth about our industry: insurance is a lever. It has no force on its own, but it can transform other parties’ risk into premiums and those premiums into positive change – first in the form of shared safety nets and second as an incentive structure for good behaviour.

Applying this to the maritime sector, it’s clear insurers cannot force shipowners to grow a social conscience. But once firms start to face some level of risk from their poor ship-recycling practices – some threat of real reputational or financial damage – then insurers will have something to work with. Right now, “ESG risk” in shipping is limited. However, to see how quickly it could become a factor, we only need look at what has happened in other industries.

Over recent decades, major energy, logistics and manufacturing brands – both B2B and B2C – have been remoulded by consumer pressure, both directly and as referred through investors, lenders and partners. A lack of widespread industry reporting has so far shielded shipowners from much of this change. However, greater ESG transparency is on its way. And with it greater ESG risk – and a need for reliable ESG solutions.

Driving transparency on ESG metrics will lead to more responsible shipbreaking

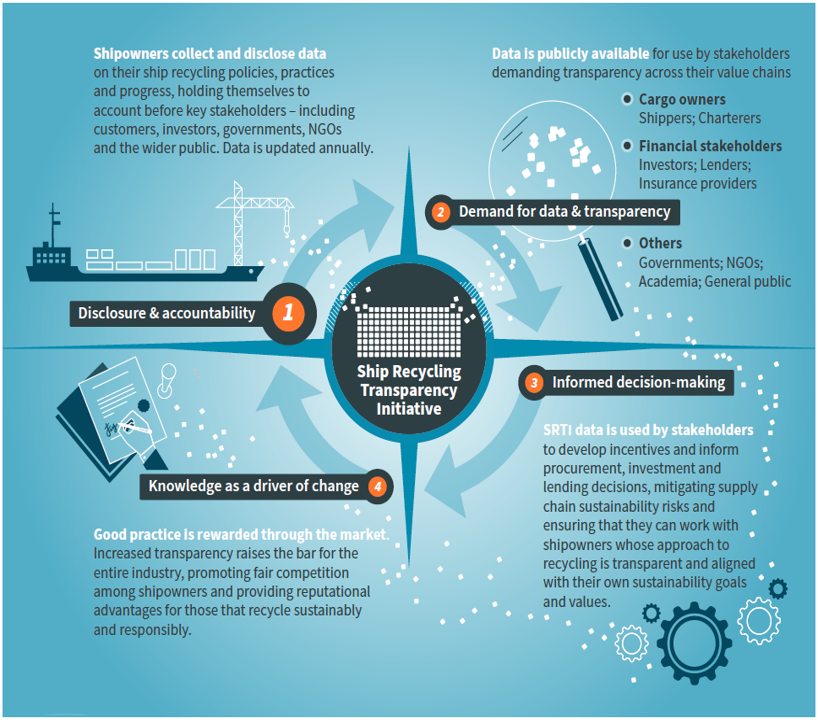

One programme embedding greater transparency into the sector is the Ship Recycling Transparency Initiative (SRTI). Hosted by the Sustainable Shipping Initiative, this is an information-sharing platform that connects shipowners to their wider ecosystem on the question of ship-recycling policy and practice.

The object is to promote competition among shipowners on ESG issues, by giving key stakeholders – including cargo owners and financiers – the opportunity to commercially reward or punish players based on their ship-recycling credentials. Investors and lenders are indeed getting serious about the greenness of their portfolios; meanwhile, cargo owners are increasingly marketing themselves to end consumers on the ethical impeccability of their supply chains, which naturally includes the vessels used to ship their products.

Shipowners cannot give their clients and financiers the same wide berth they may, at times, give regulators. And this changes the game. It transforms shipbreaking assets – full of valuable scrap steel – into shipbreaking liabilities laden with financial and reputational risk. And those who fall short on sustainability, or refuse disclosure, will ultimately be at a disadvantage vis-à-vis their competitors.

Source: Ship Recycling Transparency Initiative Progress Report 2021

To date, only 12 shipowners are signed up to the Ship Recycling Transparency Initiative (SRTI), representing ~7% of the global merchant fleet by number of vessels. But if this group can generate competitive advantages from publicising their good practice – more favourable financing terms, for example – then that could be enough to move the market.

As the consequences for doing the wrong thing mount, we expect shipping majors to be proactive in raising – and reporting on – their recycling standards. This is relatively easy to do for those of their ships they scrap themselves. But things become more complex when ships are sold on, as often happens as they age, or chartered in from another owner.

Managing third-party recycling risk via financial guarantees

Being generally less well known, second-hand operators are less exposed to ESG-related pressures than the primary owners that sell to them. As a result, they may simply act in their best economic interests, scrapping acquired vessels for high prices in substandard yards.

In these cases, ESG-conscious primary owners can find themselves still contributing, indirectly, to the social and environmental toll of shipbreaking. Indeed, the narrow focus of some ESG policies on owners’ direct footprint only has long been a bone of contention.

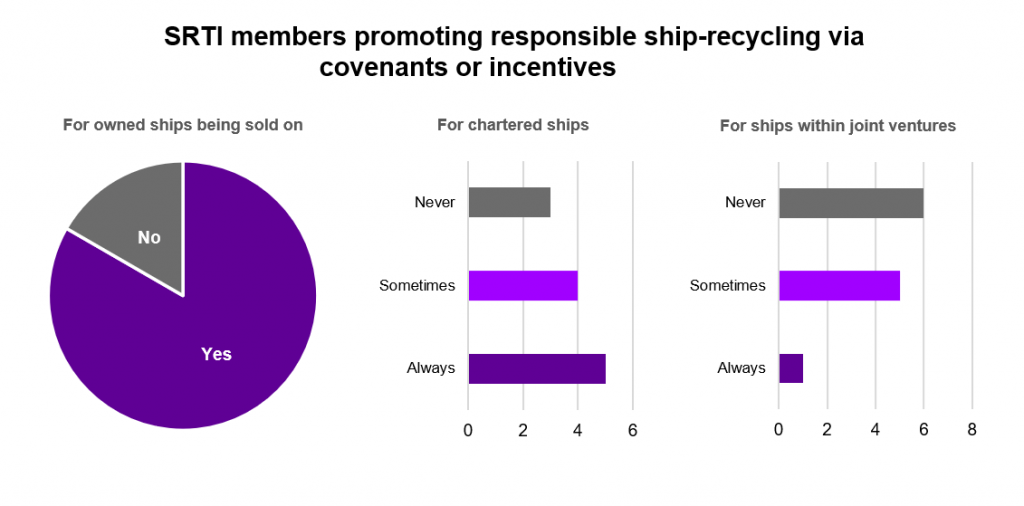

One solution is to incorporate restrictive covenants into vessel sales, stipulating where and how new owners must recycle their second-hand ships. Another is to offer buyers some form of financial incentive for responsible scrapping. 10 out of 12 of the shipowner signatories of the SRTI use one or both mechanisms to drive better outcomes for sold-on ships, in some cases extending this to vessels they have chartered and then returned to the original owners:

Source: Ship Recycling Transparency Initiative Progress Report 2021

Both mechanisms come with their problems. Covenants may be unenforceable or susceptible to loopholes, and further complexities arise in the event that a vessel is sold on a second time; incentives meanwhile may not be sufficiently compelling.

To be failsafe, a responsible-recycling incentive needs to reimburse second-hand owners for whatever proceeds they sacrifice by choosing a higher-cost regulated shipyard over an unregulated one. It must merely cover a gap – but a gap that fluctuates wildly, depending for one on the price of steel. And where there is uncertainty, there are potential niches for insurers.

It would be possible to structure a ship-recycling fund with both a savings and a premium component, the latter guaranteeing that, at the time of scrapping, the accumulated savings are sufficient to cover the gap between the best scrap price and the most responsible one. What we end up with is an endowment or whole-of-life policy – only for a ship, not for a person.

Insurers migrating to the cloud at scale are gaining savings and agility across the insurance enterprise. Find out more in our latest report: Reimagining insurance: The new cloud imperative.

LEARN MOREIf the recycling fund could be linked to a specific vessel, potentially via a distributed ledger, it would then function as an escrow – paying out only if the final owner met the agreed ship-recycling criteria. This would allow primary owners to guarantee the existence of a strong financial incentive to do the right thing by their vessel, not just for second-hand owners but for all subsequent owners.

Clearly, such a product would be fraught with challenges, especially given its open-ended duration, the potential for long chains of ownership and underlying market risk – but the idea is intriguing enough to have warranted recent discussion by the European Commission.

Insurers have the credentials to innovate around financial guarantees, but whether appetite outweighs impracticalities in marine insurance remains to be seen. What’s clear already though, if we cast our eye more widely, is that unforeseen recycling costs are a major reason for corners being cut during recycling. If financial institutions, governments and manufacturers can find a mechanism for hedging these, it will lessen perverse incentives in the user base and considerably boost the circular economy.

Returning our gaze to the maritime sector, we see that ships are not alone in having a troubling end-of-life story… In the next installment of this ongoing series, we turn our attention to offshore energy and how insurers can help with the unwinding of old carbon assets and smooth the launch of offshore green energy.

If you’d like to get in touch in the meantime, please reach out to me.

Get the latest insurance industry insights, news, and research delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe