Other parts of this series:

In our previous post, we outlined some of the forces slowly reshaping marine insurance, including cost pressures and a greater focus on sustainability in the maritime sector as a whole. Today, we explore what sustainability looks like for the shipping industry and how it both impacts, and can be impacted by, marine insurers.

Over recent decades the shipping industry has made strong progress, codified in a series of international agreements, on both environmental and human fronts – and the result has been a steady diminution in vessel founderings, spillages and lives lost at sea.

In force since 1980, the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) sets minimum standards for the construction and equipment of merchant ships. A similar convention (MARPOL) legislates for pollution arising during a vessel’s operation and, more recently, IMO 2020 has further reduced the limit for sulphur content in fuel oil.

It would seem like every part of the shipping value chain is yielding to progress, bit by bit. And this is almost true. Vessels are cleaner and safer on every voyage they take, barring their last.

Estimating the environmental footprint of shipbreaking

Many of the advances we outline above have been driven – or at least facilitated – by economics. Simply put, it makes business sense to waste less energy, and to have fewer and better-trained crewmembers. However, economics as a force of change is a double-edged sword. For it also drives shipowners to seek the best prices when it is time to scrap their vessels, a decision with a hefty human and environmental toll.

Scrap values can be substantial, due to the metal that vessels are built from. And the highest prices are generally offered by shipyards using the lowest-cost methods of dismantlement, or by hull traders planning to resell to such shipyards. Shipowners are in a position to take the money and run, with little heed for the downstream consequences.

Low-cost yards are low-cost for a reason. Typically, hulls are dragged up onto beaches and “broken” through manual labour. Workers (including children) often lack basic training and healthcare, and the requisite environmental precautions for dealing with the toxic substances contained in old ships are, again, often absent.

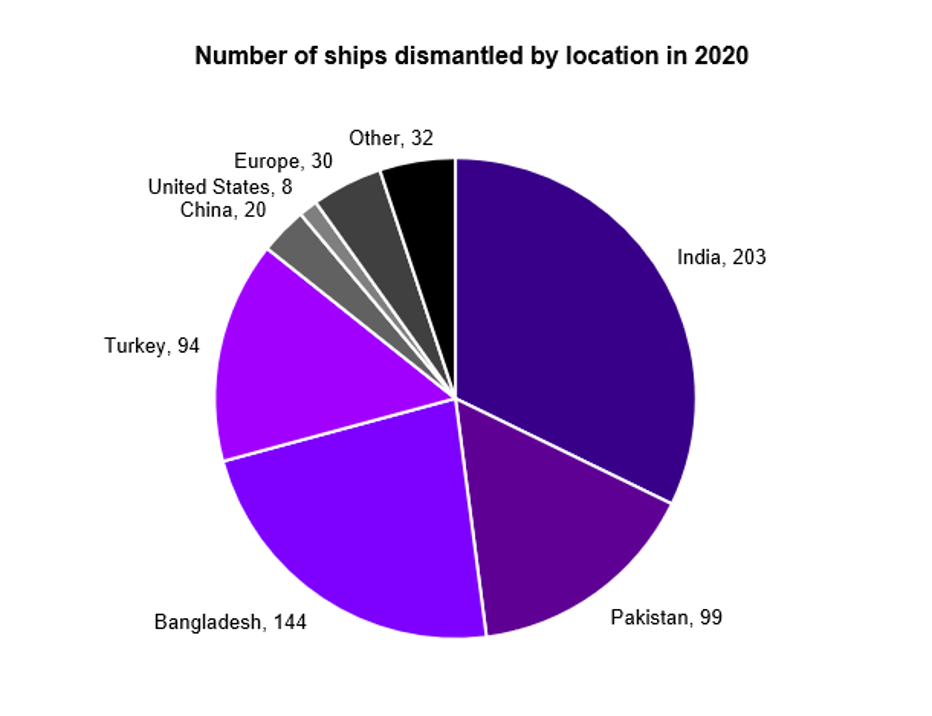

As a result, the high scrap price realised by shipowners when they send a vessel on its final voyage comes at a massive cost – more often than not incurred on the beaches of the Indian Subcontinent, where 71% of 2020’s end-of-life vessels (by number) were torn apart.

Source: NGO Shipbreaking Platform

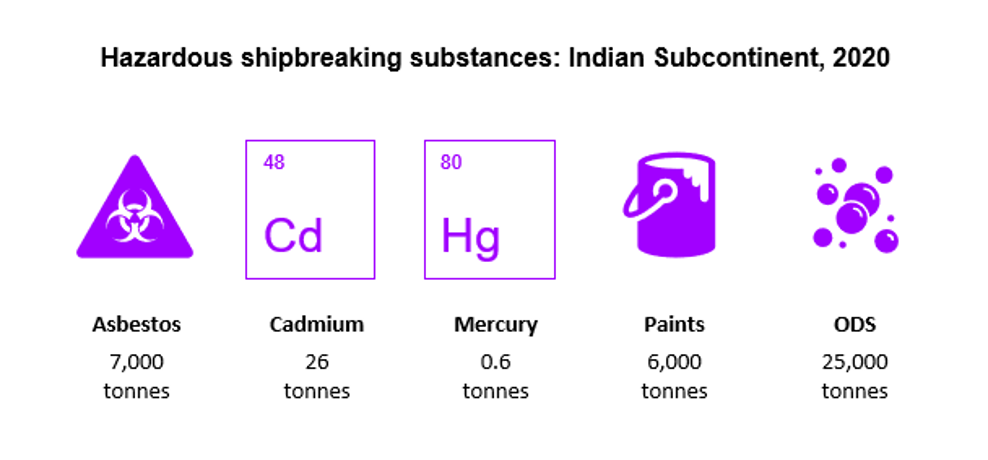

Cumulative exposure to toxic chemicals harms communities and ecosystems alike, with devastating implications for local biodiversity, fisheries and the food chain. Besides oil and sewage, old hulls may harbour any number of dangerous contaminants, from asbestos, toxic paints and ozone-depleting substances (ODS) to heavy metals like cadmium and mercury.

We estimate that subcontinental yards processed thousands of tonnes of asbestos, paints and ODS in 2020 – of which we can expect a significant portion was directly exposed to the environment.

Source: combining data from the NGO Shipbreaking Platform and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / World Bank

Structural factors continue to confound industry action on ship recycling

While the above stats may make for grim reading, this is not to say that attempts aren’t being made by the industry to drive better ship recycling.

The Hong Kong Convention, ratified in 2009 but yet to come into force, stipulates that vessels must have an inventory of hazardous materials and that shipyards must provide a recycling plan for each vessel they process.

There is also the EU Ship Recycling Regulation (to which standards the UK still adheres post-Brexit), which has required since the start of 2019 that all EU-flagged vessels be recycled at a facility on the EU’s approved list. While these yards are safer and greener than their unregulated counterparts, they naturally come with higher running costs and offer lower scrap prices as a result.

The problem with these initiatives is the ease with which ship sellers can sidestep them via “flags of convenience” and other loopholes.

At little cost, shipowners can escape recycling liabilities by switching flags to what might best be described as a regulatory haven – popular choices include Comoros, Palau, Bahamas, Panama and Liberia. This certainly appears to have happened in the case of recent EU regulation, with few ships having been recycled in accordance with the new standard. Many end-of-life vessel owners have simply “flagged out” so as to chase the highest bidder.

To be effective, regulations require broad cooperation – and the exertion of pressure – across the industry. And this is somewhere insurers can play a role.

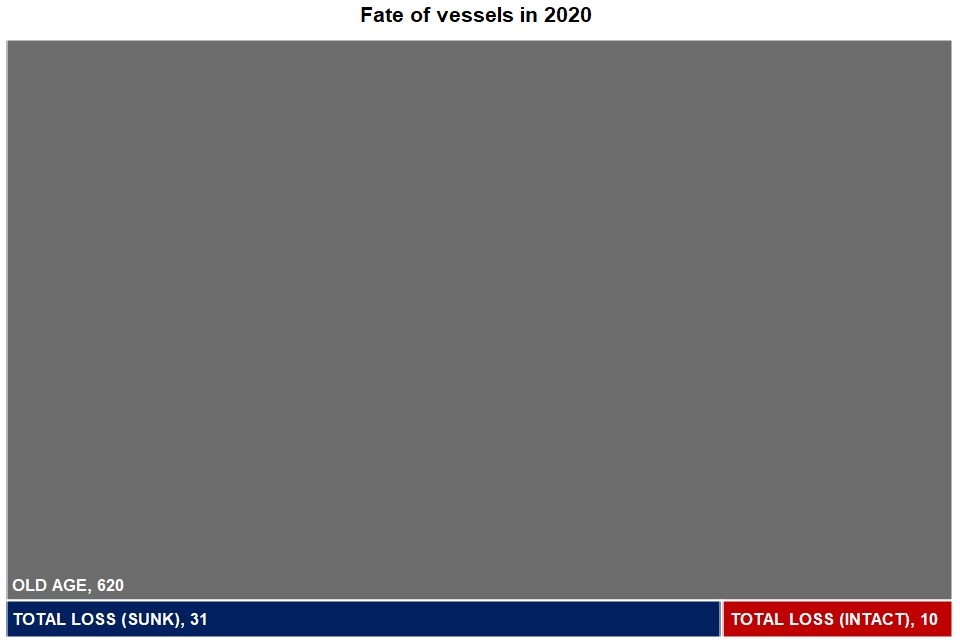

On rare occasions, insurers themselves end up as the final owners of a vessel, when the hull is a write-off but hasn’t sunk. In these cases, there is a chance to ensure the vessel in question is ethically disposed of. However, this applies only to a tiny fraction of the shipbreaking market, since the near totality of vessels is scrapped not due to an accident but rather old age.

Source: combining data from the NGO Shipbreaking Platform and Lloyds List Intelligence

In conventional scrapping cases, it is hard to see how insurers can exert much control, if any, over vessel disposal. Of course, they can take a hard line with clients, requiring that they have baseline ship-recycling policies in place before granting cover. They can also refuse final-voyage coverage if it’s clear the vessel is being towed for scrap to a substandard yard – although these final voyages can often be disguised as something else.

As with rules on the regulator level, these provisions are difficult to enforce in practice. And, even if they can be made effective, bad actors will always be able to get insurance for their ships – and for those ships’ final voyages – elsewhere. But if, here and there, the frictional cost of doing (bad) business can be increased, it will start to make those end-of-life flags of convenience look anything other than convenient.

We continue our exploration of the role that insurers, and financial institutions more broadly, can play in maritime sustainability in our next post, including transparency initiatives, ESG-linked incentives and financial products for funding the responsible recycling of ships.

If you’d like to get in touch in the meantime, please reach out to me.

Get the latest insurance industry insights, news, and research delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe

Disclaimer: This content is provided for general information purposes and is not intended to be used in place of consultation with our professional advisors.